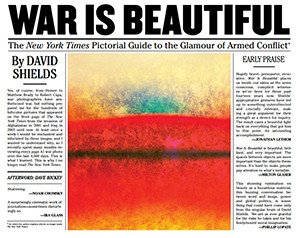

war is beautiful - david shields - review & interview rik moors

David Shields has created one of this year’s most thought-provoking collections of artful photography. “War is Beautiful” is both a pamphlet on the dangers of representing war as ‘corporate folk art’ and a museum-quality catalogue of front page news images of conflict photography lifted from the New York Times. The layout of the book is very simple, and very elegant. One could call it ‘beautiful’. Drawn in by the abstract, filmic ‘front page’ of the book, you are treated to page after gorgeous page of stunning photographs. The text is kept to a minimum, with quotes and commentary from other authors taking up more space than Shields’ own introduction. The simplicity of the layout helps draw the attention to the photographs, and lets them speak for themselves.

The only extensive editing Shields has done, comes in the form of the thematic categorization. The book is divided up into ten categories – Nature, Playground, Father, God, Pieta, Painting, Movie, Beauty, Love and Death. I asked him whether these themes jumped out at him immediately, and whether there were any particular themes which he felt were overwhelming. He explained that he had been reading the NYT for decades, and that he had slowly become aware of those themes as part of what he referred to as a ‘playbook’ that the editors and photographers seemed to adhere to. The most jarring and persistent theme is that of the Painting – a style which is perversely pervasive.

Photo Credit: Damir Sagolj/Reuters

Presenting a decade of front page NYT war photography in this manner, the book effectively condenses Shields’ personal experience over the years into one swift, velvet-gloved punch to the gut. Taken separately, each picture could have been printed on the cover of a military recruitment pamphlet. Taken together, the photographs make you feel guilty for enjoying their magnetizing aesthetic appeal, once you stop to consider the subject matter.

One thing that is interesting about the book is the way it is not just a book about war or war photography, but a direct take-down of the New York Times – a newspaper and an institution. Often considered either centrist or even liberal in the American media landscape, the NYT has been seen, and loves to see itself, as a very important opinion leader. In the book, and in my interview with the author, positive and negative descriptions of the NYT which capture this (self-)importance crop up regularly. The NYT is the Grey Lady, or the Typhoid Mary of Journalism. It is the Commissar of the Real, producing all the news that is ‘fit to print’, creating the ‘first draft of history’.

In the book, Shields explains that the NYT has been motivated at least since WWII by a frenetic need to ensure that ‘the center must hold’ – the paper of note has to maintain its quasi-neutral, pseudo-impartial image, it has to maintain its central role in US culture, and in so doing, it is trying to be all things to all people.

I ask him about the influence of the polarization and the fractionalization of the American media landscape. On the one hand, you have right-wing media institutions, politicians, and opinion leaders condemning the MSM – the Main Stream Media – a phrase that has almost become an insult in itself, and which certainly covers the New York Times. On the other hand, you have non-traditional and non-American media overtaking print newspapers like the NYT in its importance. People no longer consume media as they used to, and as a result, attempts by the NYT to write the ‘first draft of history’ seem antiquated and ineffective. Does it even matter what the NYT prints today? And how can they find a space for themselves in the Center, if that Center seems to have all-but disappeared?

Shields acknowledges these trends in US news coverage. Partially, he suggests, the rightward pull of other media and the militaristic zeitgeist since 9/11 have caused the NYT to have a very pro-military bias. ‘Liberal’ in many respects, the NYT is unwilling to openly state its political leanings, and in trying to remain centrist in a militaristic environment, overcompensates by rallying around the flagpole. The fact that 9/11 happened in New York, which made it feel very close to home for the NYT, also contributed to the nature of their coverage. In the end, it resulted in the NYT becoming an opinion follower rather than an opinion leader.

Despite facing the NYT head-on with his book, Shields stresses that he does not simply want to finger-wag at the NYT. He ‘doesn’t envy’ their position, and he certainly doesn’t think the paper is unique in their approach. He says he could have written this book about the Washington Post, or many other major American newspapers. As he states in his introduction, it is not an attack on a single paper, as much as it is a wake-up call to everyone who consumes the news thoughtlessly, and in so doing becomes culpable.

At this point during our Skype chat, the connection starts to cut off. He jokes about the Times being behind it. I laugh, but secretly, I am starting to get a little paranoid. The Times sure seems a lot more sinister after today… We move on to some topics unrelated to Typhoid Mary for a moment.

One of the main criticisms aired by reviewers of the book so far (interestingly excluding the NYT – they haven’t as of yet reviewed or spoken to Shields about the book directly), is about the assumption that Shields equates beauty with acquiescence or support. Isn’t the context that the articles provide important? Couldn’t the NYT simply use beautiful pictures to attract attention? And how should photographers record conflict if not beautifully?

Shields insists that he is not advocating for blurry, ill-composed, or even outright gory photography to grace the front pages. He also does not support Susan Sontag’s call for an end to photography. Instead, he aims to point out a very specific type of beauty represented in the book – an anodyne, abstract-expressionist, painterly beauty which does not match the reality of conflict. Because of this, war is represented as a sterilized, beautified ‘heck’ instead of the ‘hell’ that it really is.

Photo Credit: Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images

He points to the picture of bullets featured on page 58. This is a crop of an original picture which provided much more context. The cropping down and abstract-making of the picture perfectly reflect the influence of abstract-expressionist painting on conflict photography. It does seem bizarre and intentional that a pretty, close-up picture of bullets would be the picture the NYT chooses to feature on their front page to represent conflict. The contrast with some of the iconic photographs coming out of the Vietnam War, such as Eddie Adams’ photo of a police execution in the streets of Saigon, could hardly be greater.

One of the puzzling things about the book, to me, was the inclusion in the selection of front page photographs of conflicts that did not involve American troops. It isn’t puzzling because no non-American conflicts took place during the period under scrutiny – there were plenty. The confusion stems more from my own assumptions about the core argument of the book, and about the nature of the pro-war narrative that I expected coming from the New York Times. I expected the book to make an explicit argument about the Times’ depiction of the evil nature of the enemies of the US, about the chaos of non-American conflicts, and about the moral imperative of the Americans to intervene.

David explained to me that the NYT isn’t quite that ham-fisted, and that the narrative he sees is a bit more subtle. As best exemplified in the pictures under the “God” heading, the representations of War he sees reflected in the images do not aim to draw a contrast between chaos and order. Instead, the NYT, as a pillar of the establishment and a paper desperate to support the American government, aims to represent the world outside the US borders as a world which the Americans are in control of. By making the military adventures into a movie or a painting, the NYT makes reality, and war, digestible and comprehensible.

Finally, I ask for an antidote to the anodyne corporate folk art. While he acknowledges that some foreign press has had better coverage, like the BBC and The Guardian, he hesitates to point to any specific news outlet, since it matters less who produces the news, than that it is consumed critically. As an interesting example of recent photography contrasting with NYT coverage, he points to a Dutch blogger who captured the massacre at Bataclan. Here, once again, the raw reality of the violence recorded by a citizen bystander with a camera contrasts strongly with the NYT pictures of the aftermath, which featured beautiful women mourning beautifully, in front of beautifully arranged bouquets of flowers.

His argument is as persuasive as his book is beautiful. If you are looking to change the way you view the news, War is Beautiful will help challenge your perceptions.

Rik Moors, december 2015

Photo Credit: Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times/Redux

- David Shields – War is Beautiful – powerHouse Books – ISBN 9781576877593

- Bestel het boek hier bij een bekende webwinkel: War is Beautiful

David Shields maakte een van de provocerendste fotoboeken van dit jaar – een verzameling kunstzinnige oorlogsfotografie die van de voorpagina’s van de New York Times komt. Rik Moors schreef een recensie en sprak met David Shields. We laten je hier zijn stuk in het Engels lezen, want dat is de taal waarin Rik schrijft. Neem even de moeite, want het is een uitstekende, prikkelende recensie en een goed interview ineen, en het gaat over een buitengewoon fascinerend boek.